Kutahya Museum and Malatya Museum,

KUTAHYA MUSEUM

After Iznik Kutahya is the most important porcelain center of Turkey. The first museum here began as a depot in the Vahit Pasha Library in 1945 and contained archaeological and ethnographical objects collected from the region of Kutahya. After 1960 the Vacidiye Medrese, which was built in 1314 during the Germiyanoglu period in Kutahya, was repaired and the works from the depot exhibited here. It was opened to the public in 1965.

The portal of the Vacidiye Medrese leads first into a domed vestibule and from here to the courtyard. The courtyard was enclosed with a dome during the latest repairs, and in the center is a small pool, opposite which is an arched exedra. The sarcophagus of Abdulvacid, a teacher at the Medrese, is in the exedra. On both sides of the exedra and courtyard are the domed rooms which used to house the students.

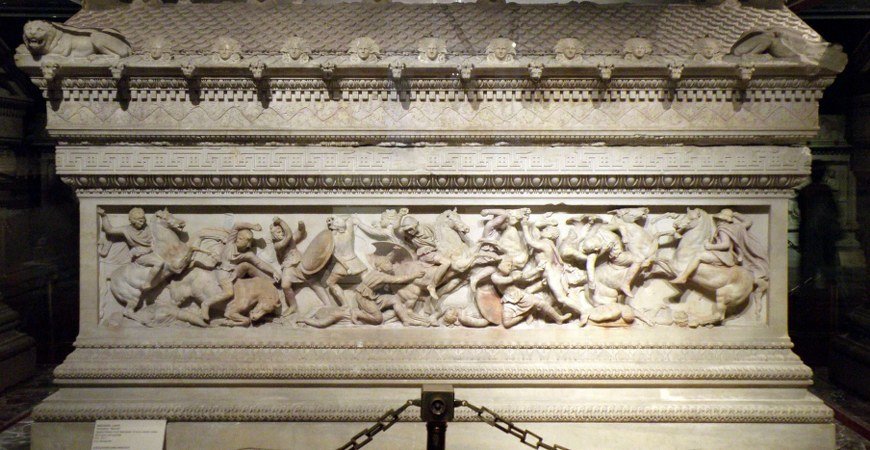

Kutahya Museum contains archaeological findings, ethnographic objects and works of art from the region of Kutahya. The archaeological works are divided into two sections : One containing works from the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods such as statues, gravestones and capitals of columns, while the other section contains stone tools and pottery from the Prehistoric Age, Hittite, and Phrygian pottery, and ceramics, lamps, small statues and coins from the Roman-Byzantine period.

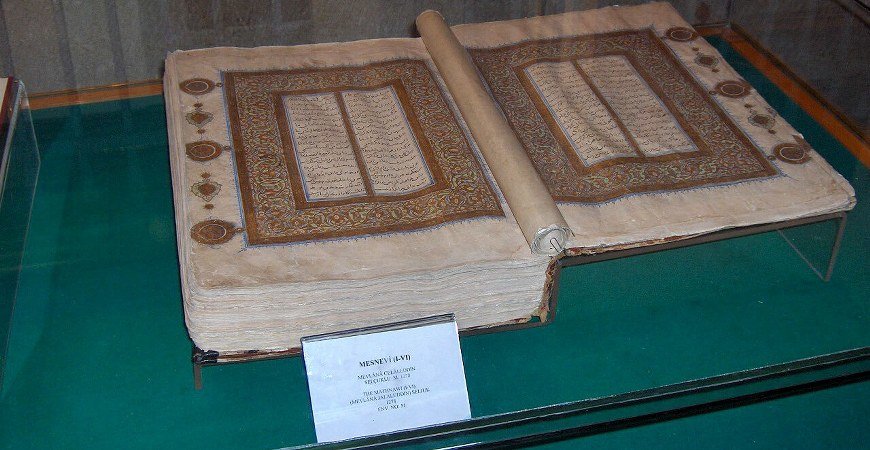

In the art and ethnographic section are examples of porcelain from Kutahya and the rest of Turkey, reproductions of wall tile decorations, and costumes, embroidery, tekke objects, weapons, copper utensils, ornaments, books etc. from Kutahya.

Pre-Islamic and Islamic period stone works are exhibited in the courtyard of the museum.

MALATYA MUSEUM

In 1969 a museum was established in the National Park in Malatya which was opened to the public in 1971. The museum contains the following exhibits arranged in chronological order:

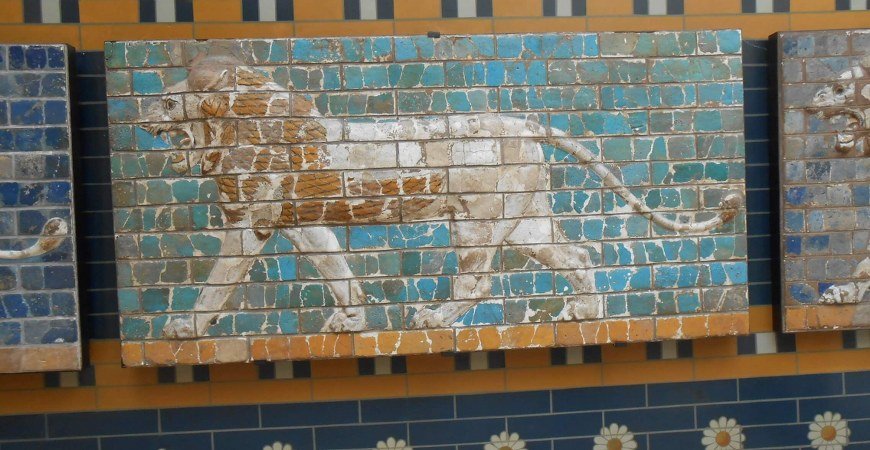

1 — Chalcolithic Age (5000-3000 BC): Clay pots and instruments made of stone and obsidian found during excavations at Aslantepe.

2 — Early Bronze Age (3000-2000 BC): A grave and clay pots decorated with geometric motifs found under the floor of a house during excavations in Aslantepe.

3 — Assyrian Trade Colonies Age (1950-1650 BC): Cuneiform cylindrical seals and stamp seals, drinking bowls and statuettes found by excavations at Aslantepe and Gelinciktepe.

4 — Hittite Age: This section contains earthenware pots, discs, pythons, stone bas-reliefs, a gold necklace etc. from the Early Hittite period (1650-1450 BC), the Hittite Empire (1450-1200 BC) and the Late Hittite period (1200-700 BC).

5 — Hellenistic (330-30 BC), Roman (30 BC-395 AD), Byzantine (395- times at Aslantepe, and Ottoman period clothes, embroidery, an ivory and coins found by excavations at Bayramtepe and Gelinciktepe.

6 — Seljuk and Ottoman Periods: Seljuk ceramics, found by excavations at Aslantepe, and Ottoman period clothes, embroidery, and ivory and mother of pearl inlaid candlestick base, medals etc.